Industrial policy is having a comeback among American wonks and politicians. There are several reasons given to support industrial policy:

ensure US dominance in industries of the future

national security

create/protect American jobs

reindustrialize the US

I’m ambivalent to the first reason1 and sympathetic to the second. I support the CHIP Act mainly for the second reason and I hope the majority Republican Congress doesn’t scrap it.

In regards to the third, the US doesn’t currently have mass unemployment although the labor force participation rate is off of its peak in the 1990s. Real median household incomes are recovering to their pre-pandemic peaks. So I don’t see a need for industrial policy to create/protect jobs in the US.

For the fourth reason, I’ve established I am skeptical of the American deindustrialization narrative in a previous post. Someone pointed out the steel industry as a counterpoint. I replied that the American steel production has fluctuated since the early 1980s, but has fluctuated in a bounded range.

But it does appear that US steel production has steadily declined since the recovery from the global financial crisis. Zooming out to examine global steel production and China is clearly the leader. China accounts for over half of global steel production. They’d need to produce a lot of steel given the amount of infrastructure they’ve built. No one else even comes close. The US is in 4th with about 4%.

Since steel is an input for many things, including defense-related products like tanks and ships, I decided to research the industry and see what could be done to improve the industry.

The structure of this post will be:

How steel is made

Economic facts about the state of the steel industry

Historical US industrial policy to support the steel industry

Recommendations

How steel is made

To understand the steel industry, it helps to have a high-level understanding of how steel is made. There are two main paradigms for steel production.2

Integrated Mills

The first is the integrated mill. In these massive complexes, metallurgical coal is heated into coke, then mixed with iron ore in a blast furnace to make pig iron. Next, the pig iron goes into a basic oxygen furnace where oxygen is pumped through molten pig iron to reduce the non-iron content and produce liquid steel. Different elements can be added for different products, but that is the gist. The vast majority of metallurgical coal and iron ore is sourced from US mines.

Steel from these types of plants tends to be high-quality and is used in industries where that is critical, like automotive manufacturing. Integrated steel plants are concentrated in Indiana, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. You might’ve seen one if you’ve ever visited The Pitt. There are two US companies operating 12 integrated mills in the US: Cleveland-Cliffs and U.S. Steel; the latter of which is having some problems. Over the last 5 years, integrated mills accounted for 28%-30% of American steel production. The workforces in these facilities are unionized.

Mini-mills

The other mode of production is the mini-mill. In these mills, electric arc furnaces are used to melt scrap metal (and sometimes sponge iron) into steel. Most of the scrap metal is sourced within the US, but the item the scrap metal comes from could be imported.

Mini-mill production is more spread out geographically and usually have non-union workforces. In 2024 there were 49 companies with 104 mini-mills. Mini-mills production took off in the 1980s and comprised about 70% of US steel production over the last 5 years.

Rolling mills

Liquid steel is then poured into casts to cool.3 After that it is off to a rolling mill where it gets finished and shaped into either flat products (e.g. plates) or long products (e.g. bars).

Steel Economics

Demand

The main consumer of steel is the construction industry and most of the consuming industries are either high capex or have expensive products (e.g. automotive). This makes the steel industry highly exposed to swings in those sectors. Say interest rates rise, it costs more to finance new high rises and demand for steel drops. Low production relative to capacity means low or negative profitability so plants want to be producing near capacity. Pausing production at a plant can be very expensive.

Employment and Productivity

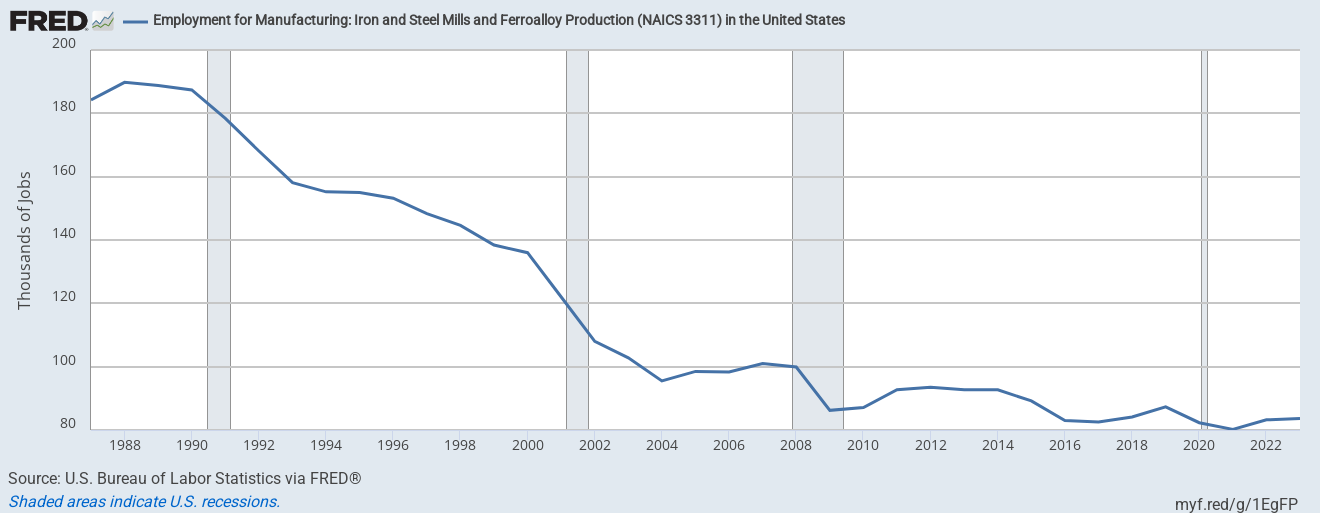

Employment in the sector steadily declined from the late-1980s to 2010 and stayed roughly steady since then. The roughly 80,000 people working in the sector are less than 1% of total manufacturing employment in the US.

This decline in employment did not lead to a commensurate decline in industry output as productivity4 rose until 2016. I believe the fall in productivity was due to COVID, so I believe the data will show productivity recovering when it is available.

This increase in productivity was due to the rise of the mini-mill. Both because of the new technology, but also the increase in competition incentivized integrated mills to be more efficient and less efficient firms shuttered operations.

Trade

The US produced about 80 million metric tons of steel in 2024 and imported 26 million metric tons. Four countries make up about 60% of US steel mill product imports Canada (22.7%), Brazil (15.56%), Mexico (12.18%), and South Korea (9.72%). It exported 8 million metric tons of which 90% went to Mexico and Canada. America does seem to have an advantage in producing high grade steel, which is important in some applications like automotive manufacturing.

Most of the trade is in flat products. Imports have fallen by 24% since 2017, while exports have been pretty flat. It makes sense that most of the trade is with Canada and Mexico. The gravity model of trade predicts this. Also, our supply chains are very connected, particularly in automotives. Shipping heavy products like steel can be expensive, so that is another factor keeping most of our steel trade in the Western hemisphere.

Price Competitiveness

US steel prices spiked coming out of the pandemic lockdowns, probably due to supply chain issues. Despite coming down from the peak, they’re still above pre-pandemic levels.

At the time I checked this source, US HRB5 steel was 2.6x more expensive than Chinese steel ($1,009 vs $381 per metric ton). But China is forced to dump steel at bargain prices because of a slump in domestic demand and is not a good point of reference given differences in income and costs.

Western Europe is a better reference point. The US was 1.4x more expensive than Western Europe ($1,009 vs $740 per metric ton). I couldn’t find a smoking gun for why. Electricity is cheaper in the US than Europe overall, which is a major input for EAFs. Coal is cheaper in the US than Europe which is an input to integrated mills. Iron ore prices seem to be close in both places. I tried to find comparisons of shipping/rail costs between the US and the EU, but couldn’t find anything solid. Labor might be part of the difference since US incomes are higher than in Europe. Still, I don’t know why US steel is comparatively expensive.

Historic US Industrial Policy

Most US steel industrial policy has been in the form of protectionism. I highly recommend you read pages 18 to 24 of this report. Protection for US steel began in earnest in the late 1960s.

The US signed the 1968 Steel Voluntary Restraint Agreement (VRA) with Europe and Japan to limit their steel exports to the US. The agreement was updated in 1972 to allow for more imports. In 1984 a VRA was signed with 29 countries to limit their steel exports to the US.

The US has used anti-dumping duties (AD) and countervailing duties (CVD) to combat steel sold below cost and subsidized steel, respectively. Since 1968, there’ve been 272 investigations for potential use of ADs and CVDs.

From 2002 to 2004, various types of steel imports were tariffed at 15-30% and any imports over 6 million short-tons were tariffed at 30% for select products. Economist Lydia Cox studied the effects of this short period of high tariffs. She found negative effects on exports and production in downstream industries. Moreover, the negative effects on downstream exports persisted, even after the tariffs and prices returned to normal due to costs importers face when changing suppliers.

During the first Trump administration, he used section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act to put 25% duties on steel imports from most countries6 on national security grounds. These were rolled back under Biden, but tariff rate quotas7 took their place. The 25% tariffs on steel have been put back on in the second Trump administration and no countries are exempted.

In addition to keeping out competition, the US supports demand for US Steel through the Buy American Act of 1933. This requires a minimum of 55% of a federal purchase to be sourced domestically by value. Given the comparatively high cost of American steel, this drives up costs. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act extended the buy American provisions so that all steel bought for the projects be sourced from the US and most of the steel in components or machinery must be domestic steel. Given the rising costs of interest payments on American debt, increasing costs may not have been an good idea.

In the Peterson Institute for International Economics report the author gives American industrial policy to support the steel industry bad grades across the board. Given that US steel is not price competitive, output is mostly flat, and employment in the sector has gone down, it is easy to see why. Most of the productivity gains in preceding decades was brought on by the mini-mill, which was a private sector innovation. The costs have been staggering. From page 23 of the report:

Moreover, the cost paid by steel users per job “saved” in the steel industry has been stratospheric. US consumers and businesses are currently paying more than $900,000 a year for every job saved by Trump’s steel tariffs, extended by Biden.

In turn, this high cost has curtailed output and employment in downstream industries. According to one analysis, President Trump’s Section 232 tariffs might have slashed employment by 433,000 jobs in the rest of the economy while increasing employment in the steel industry by just 26,000 jobs over three years (Francois, Baughman, and Anthony 2018). Nevertheless, since benefits of protection are concentrated while costs are widely distributed political arithmetic strongly supported the Section 232 tariffs.

Recommendations

I recommend the following:

US should negotiate with friendly countries to reduce tariffs and duties on each other’s steel production and coordinate anti-dumping duties against Chinese steel. This is the friend-shoring approach. Perhaps increased competition will drive innovation, as the rise of mini-mills did in the integrated mills. It is clear that tariffs have not started a renaissance in American steel production and have costs in employment and production in steel consuming industries.

Allow Nippon Steel to acquire US Steel. The Biden administration was wrong to block it for national security reasons. We do not live in the 1940s or the world of Debt of Honor. Japan is an ally. The deal would save steal production and jobs and bring vitality to the integrated mill part of the steel sector. US-located steel production would benefit from the $400 million Nippon steel spends on R&D (compared to ~$40 million by US steel).

The American steel industry doesn’t put a lot of money into R&D, comparatively. The government should step in to fund research on improving steel production, both directly and through university grants. It was already doing this for reducing carbon emissions in steel manufacturing through the Department of Energy's Advanced Manufacturing Office. Increasing energy efficiency would lower US steel prices at the margins; particularly for mini-mills using EAFs. Additional projects on increasing productivity should be funded as well.

Repeal the Jones Act. The act requires all domestic seaborne shipping to be conducted by American built, crewed, and owned ships. This reduces the supply of ships available to move goods (including steel) within the US, which drives up shipping costs. This can divert scrap metal from American mini-mills to foreign ones. It drives up costs for consumers of American steel depressing demand.

Unfortunately, protection for the steel industry is politically popular. Perhaps the recent tariff turmoil will change public opinion, but I doubt there is appetite in the current administration for recommendations 1 or 4. Given DOGE’s slash and burn approach, I don’t hold much hope for recommendation 3. I’m still holding out hope the Nippon-US Steel deal will go through.

I doubt my recommendations would lead to levels of steel production seen in the mid-century, but I do think they would help on the margins. Repealing the 25% tariffs are particularly important because they are hurting demand in downstream industries. This is not good for steel production.

There is a sliding scale for industrial policy from dumb to smart. At the extreme of the dumb end is melting down pots and pans in backyard furnaces. 25% tariffs are not as dumb as that, but are on the dumber side of the spectrum. I think we can move over to the smart end if there is the political will.

There is a vigorous debate on the efficacy of infant industry protection. I don’t have strong opinions either way.

This source provided a lot of background for this post.

The same general shape holds for both labor productivity and capital productivity.

A grade of hardness

Mexico, Canada, and Australia were excluded.

Tariffs that kick in when more than X amount of a good is imported