Is America Really Oil Secure?

International Conflict, Global Markets, and Trump's Pursuit of Oil Dominance

This is the first part of a series exploring various parts of the energy sector under the second Trump administration. All opinions on this blog are mine and mine alone.

Late last week, Israel initiated strikes on Iranian nuclear, military, government, and energy facilities over concerns about its nuclear program. Iran has responded with missile and drone barrages. I outlined this possibility in a previous article about a potential US-Iran nuclear deal, but thought it unlikely. As threats of a greater regional conflict loom, oil prices have jumped, which is evident in the forward curve for oil futures.

Now seems like a good time to ask, “Is the US oil secure?”

The Trump administration does not think so. On the day of his second inauguration, Trump signed Executive Order (EO) 14156 declaring a national energy emergency. This document and subsequent Executive Orders (EOs) suggest that the US faces a crisis of energy security, with the oil industry being of particular concern. Energy security is access to a steady supply of affordable energy, so oil security is access to a steady supply of affordable oil. Oil security is top of mind for governments for economic and strategic reasons. The 1973 oil crisis sparked a global recession and a prolonged period of stagflation. Japan decided to attack the Dutch East Indies and the US in 1941 after the US embargoed oil and gasoline going to Japan. So, back to the question, “Is the US oil secure?”

The month before the 2024 election, the US produced a record 13.45 million barrels per day (bpd) of oil. In March of this year, it hit another record at 13.49 million bpd. The US is the largest oil producer and has been for the last 7 years. It’s even a net exporter.

But concluding the US is oil secure because it produces a lot of oil is myopic. While the US is the largest oil-producing country, it accounts for a fifth to a quarter of global production. This means it does not control the price of oil and is vulnerable to price shocks. EO 14156 correctly identifies this risk:

In an effort to harm the American people, hostile state and non-state foreign actors have … abused their ability to cause dramatic swings within international commodity markets.

We have two examples of international conflict-driven oil price shocks in the post-Shale Revolution world.

Russian Invasion of Ukraine

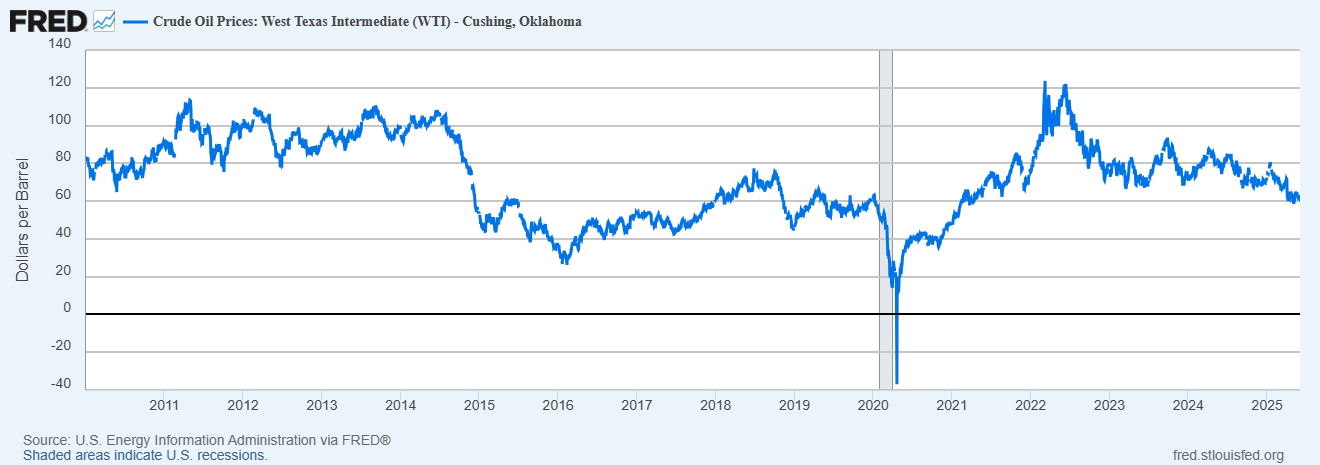

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, oil prices plummeted as economic activity ground to a halt. At the same time, a price war ensued as OPEC attempted to punish Russia for its refusal to cut production.1 Plummeting oil prices caused US production to fall 3 million bpd from 12.8 million bpd between March and May 2020. For most of 2020 through the first half of 2022, US oil production stayed about 1-2 million bpd below the pre-pandemic levels. Coming out of the pandemic lockdowns, demand rose faster than supply, and oil prices rose. Then Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. Oil prices shot up, with WTI crude peaking at $123.64 in May 2022. The US hadn’t seen oil prices like these since 2014.2

But oil prices retreated from their May 2020 peak amid recession fears and increased OPEC production. Before the Israeli strikes on Iran, oil prices were near their nominal prices right before the pandemic. This is evident when I add the last couple of years back to the graph.

Just as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine shows how international conflict can cause a spike in oil prices, we are seeing a repeat of this due to the events in the Middle East.

Israeli-Iranian Conflict

Liberation Day drove oil prices down about $10 a barrel by increasing uncertainty about global economic growth. The Israeli-Iranian conflict has erased that price drop.

Prices haven’t reached their 2022 highs, but it has only been three days. There is the potential for continued strikes on the energy infrastructure of both Iran and Israel, which would reduce supply. Merely a threat from Iran to target shipping through the Strait of Hormuz could send oil prices dozens of dollars higher, as around 20% of global oil flows through there. This would also rock natural gas markets. Most of the oil transiting through the Strait is bound for Asia, threatening their supplies. Although the US has a sufficient supply, it would still suffer from increased prices.

Strategic Petroleum Reserve: A Buffer Against Shocks

The US has the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR). The US created the SPR after the 1973 oil crisis, in which OPEC embargoed the US, among others, for its support of Israel in the Yom Kippur War. The crisis led to the creation of the International Energy Agency, which requires members to have at least 90 days of import reserves. As of June 6th, the US has 402.1 million barrels of crude stored underground at four sites near refining and distribution networks along the Gulf of Mexico. With American daily oil consumption at 20.25 million bpd, that is a little under 20 days’ worth of oil.3 The US imports 6.48 million bpd, so that is 62 days of imports covered. The SPR, along with private reserves, allows the US to blunt any upward price shocks for a time. Biden did just that in 2022 after Russia invaded Ukraine.

The SPR mitigates the risk of a 1973 or 1979 spike in oil prices for a time, but consumers would still face higher prices. A prolonged conflict is still a major threat to the affordability of oil. While reserves can blunt short-term shocks, long-term oil security depends upon federal policy.

Trump Administration’s Oil Security Strategy

So far, Trump’s executive orders affecting the oil industry have focused on directing relevant agencies to expedite environmental reviews and cutting rules and policies deemed burdensome on energy projects. The One Big Beautiful Act would open up federal lands and waters to more drilling. Additionally, it would end electric vehicle (EV) subsidies, pushing people towards gasoline-powered vehicles. Last Thursday, Trump undid California’s electric vehicle mandate. The cumulative effects of these policies are to make it easier to “drill baby, drill” and increase future oil demand to induce oil companies to pump more oil. But, the administration’s trade policy is working at cross purposes to its desire to produce more oil. Oil producers import parts, machinery, and equipment, and domestically made equipment is impacted by tariffs on intermediate goods, like steel. Sustained higher prices may overcome the higher costs. The administration’s policies may well induce higher oil production.

Assessing the Path to Oil Security

I said at the beginning of this post:

…concluding the US is oil secure because it produces a lot of oil is myopic

The administration is pursuing oil security by incentivizing oil companies to increase domestic production. But increased domestic production does not insulate the US from volatility in global oil markets, as the case of Russia-Ukraine painfully demonstrated. Cutting environmental regulations may increase future supply, but knee-capping electric vehicles will increase future consumption, which still leaves the US vulnerable to price swings. To truly attain oil security, the US needs to reduce its reliance on oil. By hindering EV adoption in the US, it is possible that a future America continues to lead in oil extraction, but is less oil secure.

Russia wanted to capture market share, assuming US producers would need to stop production given their higher costs.

OPEC attempted to kill the US shale industry in 2014 by increasing production to lower prices below Shale operators’ costs. It didn’t work.

It would take several months to completely draw down the entire oil supply, as the maximum removal capacity is 4.4 million barrels per day.