Would you like to buy a Ukrainian Mine?

Trump, Zelensky, a Mineral Deal, and Investing in Fixed Assets under Political Risk

Whilst I was on going on a refreshing weekend getaway, Trump and Zelensky were having a rather heated exchange. Zelensky was there to sign a “mineral” deal, which would establish a joint investment fund between the US and Ukraine. This deal stipulates Ukraine would deposit half of future revenues from new publicly-owned natural resource assets into the fund.1 While the messaging focus is on minerals, this includes other natural resources, like hydrocarbons. The goal is to encourage more private investment in those assets. There aren’t any hard security guarantees for Ukraine in the deal, but the logic goes that high returns on this fund would give the U.S. an incentive to make sure Ukraine is secure and rebuilt. This got me thinking, “Would I build a mine in Ukraine?”

Political Risk and Fixed Assets

Assets like mines and gas pipelines are extremely capital intensive. The assets are also fixed; you can’t pack them up with you when you leave. So you have to spend a lot of money and you have to leave your money if you’re kicked out. Therefore these companies are very sensitive to political risk. By political risk, I mean the government of the country I’ve invested in says, “Give me a share of your revenues or I take over you stuff.” Or even worse, “I’m taking over your stuff with my military.” This isn’t a thought exercise; expropriation of oil assets has its own Wikipedia entry.

I mean, who can forget the Abadan Crisis? I’m sure the oil majors haven’t. This is why bribing government officials is more common in industries like mining than others with un-fixed investments. Engaging in a little light bribery is good for business; especially now that it may be legal. When property rights are more like property suggestions, keeping the local government happy makes them less likely to take your things. So how does that affect my hypothetical mine?

Investing under No Political Risk

First, I need to come up with a valuation for my mine under the assumption it can’t be expropriated (taken away from me). I need some numbers to value it. They don’t need to be too precise. Some back of the envelope calculations are good enough.

First, the costs. It costs about $500 million to $1 billion to open a mine and processing plant. There are many factors affecting the cost, but let’s go with $1 billion. Ukraine has a lot of rebuilding to do, so I’m leaning on the more expensive side.

Next, I need an idea of how long it takes for my investment to start paying off. It takes about 18 years (on average) to bring a new mine online and generating positive cashflows. Once online, I’ll assume it can run for 50 years.

Once it starts paying off, what’s the return on my investment (ROI)? I’ll say the annual return on investment in the mine will be 12.43%. Why? That was the return on equity for the metals and mining sector I got from here. That’s not the same thing as ROI, but it is good enough for my purposes.

Now, I need to discount my future cash flows. Suppose the discount rate is 4.22%, which was the yield of a 10 US treasury as of March 4th.

These numbers don’t need to be perfect. I’m not actually doing an in-depth discounted cash flow analysis for a real project; my corporate finance class sent me running back to statistics and econometrics . They just need to be in the ballpark.

Now, under some simplistic assumptions, I can value my mine. What are those simplistic assumptions? There are a lot baked in, but the two I’ll point out are:

The $1 billion investment is split evenly over the 18 years to bring the mine online.

The 12.43% return is net all costs and doesn’t vary. This is the mean case.

I wrote some R code for this analysis because I miss the language and can’t use it at work. Damn Python for eating the world.

# Set the parameters of the analysis.

cost <- 1 # Billions of Dollars

yearsToOpen <- 18

roi <- 0.1243

yearsOperational <- 50

dr <- 0.0422

# Create cash flows where the cost is split evenly over years before the mine

# comes online. Once it comes online, start providing positive cash flows.

totalYears <- yearsToOpen + yearsOperational

investmentArr <- rep(cost / yearsToOpen, yearsToOpen)

cashFlowsAfterOpen <- rep(cost * roi, yearsOperational)

discountArr <- (1 + dr)^((1:totalYears) - 1)

cashFlowArr <- c(-investmentArr, cashFlowsAfterOpen)

dcfArr <- cashFlowArr / discountArr

npv <- sum(dcfArr)Under the assumptions and conditions laid out above, the net present value (NPV) of this mine is $554 million. Not shabby, although my risk averseness/desire for diversification pushes me to being a boglehead. But what happens when I assume someone can just come in and take my mine?

Investing under Political Risk

For simplicity, I’m assuming there is an equal chance of expropriation in each time period (a year) over the life of my mine. The equal probability in each year makes each year a Bernoulli trial. Assuming the mine won’t be given back if expropriated, it only needs to be expropriated once for the future cash flows to go to zero. So each year is a Bernoulli trial and we only care about expropriation happening once. That means we can use the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of a geometric distribution to weight the cash flows. The CDF gives the probability that the mine was expropriated at or before a given time step. So I can discount the discounted cash flows by the probability I’ll actually receive them. In other words, I can look at the NPV under a range of different probabilities that someone takes away my investment and doesn’t give it back. I did just that looking at

The code I used is below. Note, if CDF(p, i) is the probability the mine is expropriated at or before the i-th year for a given p, 1 - CDF(p, i) is the probability it is not expropriated.

# Loop through probabilities of expropriation of the mine in a given year.

# Fill out a matrix with real cash flows weighted by the probability they will

# be received under a geometric distribution.

probsExpropriation <- 1:999 / 1000

weightCashFlows <- function(p) (1-pgeom(1:totalYears, p)) * dcfArr

cashFlowMat <- sapply(probsExpropriation, weightCashFlows)

# Calculate net present values.

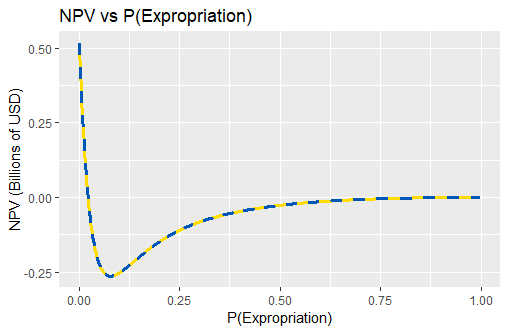

npvArr <- colSums(cashFlowMat)As you can see from the plot below, the mine quickly looks like a bad investment as P(Expropriation) increases. At around P(Expropriation) = 0.022 (approximately 1/44), the NPV goes to 0. In other words, an un-profitable investment. From there it gets more negative until it starts trending up to $0. This is because as P(Expropriation) increases, the average time to expropriation decreases. If the mine is expropriated early enough, I’ve invested less money and those 18 years of initial negative cashflows attenuate (go to zero).

Anyways, the main takeaway is a little bit of P(Expropriation) makes this an unprofitable investment for me. I’m very sensitive to any chance I'll lose my precious mine!

So is there any chance my Ukrainian mine gets taken away?

Political Risk Mitigation

Of course! Obviously, Russia could invade Ukraine again within the lifetime of the mine. They’ve done it twice within 10 years! If my mine is in Eastern Ukraine, I’m very worried about this! Russian troops could swoop in and give my operation over to Norilsk Nickel or another Russian mining company. I can mitigate this by currying favor with the current head of Russia, or an American president on friendly terms with them. Maybe I do a little bribery (again, it may be legal now) or contribute to a Trump-owned crypto coin. But they might not be in power forever and they’re not the only government who can take my mine away through a monopoly on violence.

The other main risk is Ukraine. Why might Ukraine take my mine away? They’re only signing this deal (assuming it happens) out of the hope for some form of security guarantee. If the US reneges and leaves Ukraine out there with their ass hanging in the breeze (i.e. vulnerable), why would they continue honoring the deal? There’s the corruption issue as well, but this is miniscule to a Western company when Ukraine’s security is enforced by the U. S. of A.

What can be done to mitigate my fears of expropriation, by one government or another?

Security guarantees

If I’m investing in a mine (or some other capital intensive fixed asset), it would be comforting to know another country can’t come in and send me home with nothing but whatever is in my pockets. It is somewhat nice to know that it may be legal to bribe my way out of that mess, but what if there a higher bidder who’s a part of the oligarchy of the invading country? I’d strongly prefer that the county I’m investing in is secure from outside aggression.

Strong property rights

I covered an outside government taking my mine. What if the call is coming from inside the house?! Ukraine has no incentive to abide by the terms of this deal if they aren’t protected. So what if the threat passes, but they’re still corrupt? What does that mean for my mine? Ukraine is no where near as bad as it was under Yanukovych. But it could be better. You know what would help? Forcing Ukraine to adhere to the Copenhagen criteria to the point it can join the EU (and NATO for security guarantees). Forcing it along the path to EU membership, without relaxing the requirements, would make it more in line with Western values2 (one of which is respecting property rights) and protect my mine.

Conclusions (aka Unimaginative Section Header)

In summary, I may be less inclined to build a mine in Ukraine if I think my mine has even a small chance of being seized in a single year over its operational life. The best way to encourage me to invest is to assuage my fears. Use the arsenal of democracy to let me know, with certainty, Russia won’t come in and steal all of my investment. Continue pushing Ukraine on a path to being a country with minimal corruption.

I’m not saying it’s impossible to make this deal work without concrete security guarantees for Ukraine, or enforcement mechanisms that force it to uphold strong property rights. Mining and oil companies have been investing and operating in unsecure countries with nebulous legal codes as long as the industry has existed. But you have to put on your Bayesian hat and admit, those conditions would increase my investment’s value and the success of the fund.

CSIS. I “borrowed” some of this article’s sources as my own. Everyone who’s written a college paper with source minimums has done the same thing, so don’t come at me, bro.

Western values is a vague idea that sometimes encompasses Enlightenment ideas. That’s the way I use it here.